A payer contract is a legally binding agreement that outlines the terms of covered services provided by healthcare providers and the reimbursement from commercial or government payer organizations. Its primary purpose is to ensure patients receive medically necessary care in accordance with the agreement.

When creating and negotiating contractual agreements, it is important to consider many key factors. A well-written contract should include clear language that identifies the parties involved, details the plans offered, outlines reimbursement procedures and specifies the physician services covered. Ensuring that all parties adhere to the contractual terms is crucial; failure to do so is how many contracts are terminated.

Before jumping into a review of payer contracts or devising a negotiation strategy, the following areas should be understood by practice personnel in charge of managing your contract reviews.

Key terms in payer contracts

Parties

The legal entities entering into a payer contract, typically the healthcare provider organization and the payer (health insurance company, managed care organization, or employer).

Plans

Specific health benefit programs provided by the payer and governed by the terms of the contract, detailing covered services, benefits, and patient cost-sharing responsibilities.

Products

Distinct types of insurance offerings (e.g., HMO, PPO, EPO, POS, HDHP) provided by the payer and subject to specific terms regarding network participation and reimbursement.

Provider Services

Healthcare services, procedures, or supplies delivered by contracted providers to covered members, defined and reimbursed as specified by the contract.

Credentialing

The payer’s process of verifying provider qualifications, licenses, certifications, malpractice history, and privileges to ensure compliance with standards for participation in payer networks.

Payment Deliveries and Requirements

Contractual obligations detailing reimbursement methodologies, fee schedules, timelines for payments, submission of claims, electronic payment processes, and documentation required to receive reimbursement from the payer.

Coordination of Benefits (COB)

Contractual provisions specifying how benefits and payments will be determined when multiple payers cover the same patient to avoid duplicate payments and determine primary and secondary payment responsibilities.

Dispute Resolution

Procedures established to handle disagreements or conflicts between provider and payer regarding contractual interpretation, payment accuracy, or other obligations, including negotiation, arbitration, or mediation steps.

Financial Information

Contractual provisions detailing requirements for maintaining and sharing relevant financial records, audit rights, financial reporting, and reimbursement transparency between providers and payers.

Policies and Procedures

Formal rules, guidelines, or operating standards developed by the payer or provider outlining processes for delivering services, submitting claims, obtaining authorizations, or complying with regulatory requirements.

Quality Review

Contractual provisions describing how the payer assesses the quality and appropriateness of provider care and adherence to clinical standards or performance metrics.

Utilization Management (UM)

Processes used by the payer to evaluate and approve healthcare services for medical necessity, appropriateness, efficiency, and compliance with coverage guidelines, including prior authorizations and concurrent review.

Terms of Termination

Contractual clauses specifying conditions, notice periods, reasons, and processes under which either party may terminate the contractual relationship.

Operations

General requirements regarding day-to-day interactions, communications, information exchange, reporting, record-keeping, technology interfaces, and compliance with standards necessary to implement the payer-provider relationship.

Amendments

Procedures or conditions under which the contract terms may be updated, modified, or renegotiated, including required notice periods and mutual consent provisions.

Allowed Amount

The maximum amount established by the payer that is payable to providers for covered healthcare services, including contracted rates or negotiated discounts.

Claim Submission

Contractual requirements outlining timelines, methods, coding, and documentation necessary for providers to submit healthcare claims to the payer for reimbursement.

Medical Necessity

Defined criteria that services must meet to be considered clinically appropriate, necessary, and covered by the payer under the contracted health plan.

Network Participation

Terms governing provider’s inclusion in a payer’s network, including obligations for accepting patients, adhering to fee schedules, and compliance with payer-defined standards.

Timely Filing

Defined contractual timeframe within which providers must submit claims to the payer to avoid denial for untimely submission.

Reimbursement Methodology

The agreed-upon payment models (e.g., fee-for-service, capitation, bundled payments, value-based care) used to compensate providers for healthcare services.

Examples of health plans

Understanding the types of payer plans is a crucial element of creating and negotiating payer contracts. Reimbursement methodologies are shaped by how care is delivered and the financial responsibilities of patients. Key factors such as coverage requirements, patient cost-sharing, prior authorization rules, and contract fee schedules directly impact negotiations. Let’s review the most common payer plans:

Health maintenance organizations (HMO)

HMO plans use a highly structured network model that requires patients to select in-network providers and designate a primary care physician (PCP). The PCP serves as a gatekeeper, providing referrals for specialist visits and coordinating care. Many HMOs operated under capitated payment models, where providers received a fixed per-member-per-month (PMPM rate rather than traditional fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement.

Preferred Provider Organization (PPO)

PPOs offer greater provider flexibility while maintaining a network of preferred providers who accept negotiated fee schedules. Patients do not need referrals to see specialists and can seek out-of-network care, though at a higher cost. PPOs typically use a tiered reimbursement system, meaning providers receive lower rates for out-of-network services, which has led to balance billing if the provider charges above the plan’s allowable rate.

Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO)

EPO plans are similar to PPOs but do not cover out-of-network services (except for emergencies). Members must receive care from contracted providers only, but unlike HMOs, they do not need a PCP referral for specialist visits. EPOs often feature lower premiums and narrow networks to control costs.

Government Programs

Government programs provide coverage under federally or state-administered plans with regulated reimbursement structures:

- Medicare — Covers adults 65 and older and some younger individuals with disabilities. Medicare has both traditional FFS (Parts A and B) and Medicare Advantage (Part C) plans, which often involve risk-based or value-based payments.

- Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are privately administered plans that contract with providers separately and often negotiate capitated or shared-risk arrangements.

- Medicaid — A state-run program for low-income individuals, with varying reimbursement rates and managed care models that impact provider contracts.

- Workers’ Compensation – Covers job-related injuries, with state-regulated reimbursement schedules and utilization review processes.

- Veterans Health Administration (VHA) – Government-run healthcare for veterans, often requiring providers to contract separately under the VA Community Care Network (VACCN).

Self-insured Employer Plans (ERISA)

Health plans sponsored and self-funded by private-sector employers, regulated under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Employers assume the financial risk and often contract with third-party administrators (TPAs) for claims processing and provider contracting.

- Note: Government, church-sponsored plans, and Workers’ Compensation are generally exempt from ERISA.

High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) with Health Savings Account (HSA)

Insurance plans with lower premiums and higher deductibles. Often paired with Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), allowing tax-advantaged contributions for medical expenses. Providers should understand implications for patient payment responsibilities.

Other plan types and risk models

- Point-of-service (POS) plans — This hybrid of HMO and PPO features in-network care from a PCP who coordinates care and provides referrals, though out-of-network services may be covered at a higher cost.

- Healthcare share ministries (HCSMs) — Religious-based groups where members share medical costs but are not regulated as traditional insurance. These typically will not be involved in payer contracting since ministries don’t negotiate or contract with providers directly in the typical managed-care sense.

Understanding these payer types — including their network restrictions, reimbursement methodologies, and patient cost-sharing structures — provides leverage when negotiating contracts. Many payers seek lower provider reimbursement rates for higher patient volume, while others offer value-based incentives tied to quality metrics. A well-informed negotiation strategy accounts for payer mix, plan design and reimbursement trends to optimize financial outcomes.

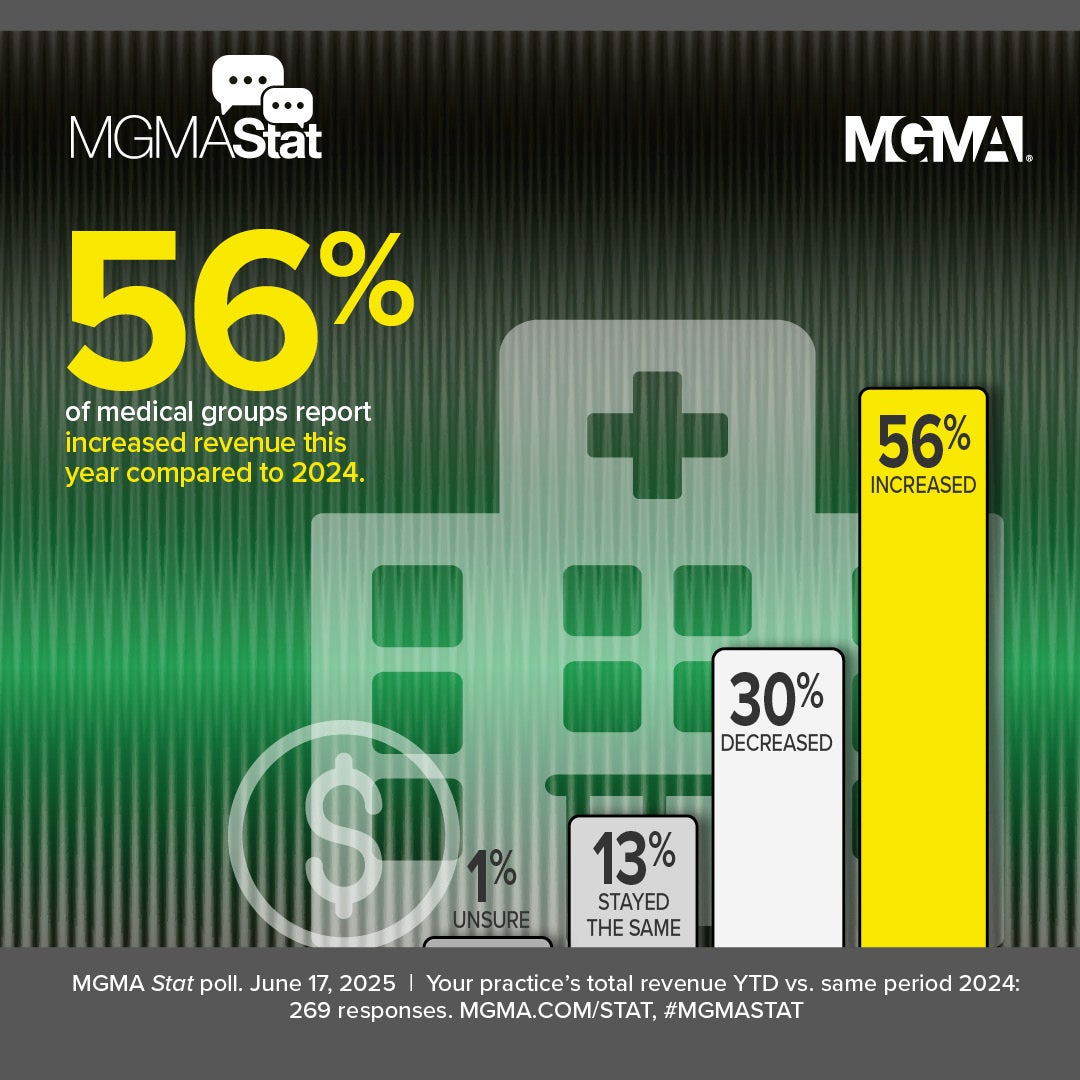

Why it matters: Payer mix

Different payers reimburse at varying rates, and a practice heavily reliant on lower-paying contracts may struggle with profitability. By analyzing payer mix — the percentage of revenue from each payer, reimbursement trends, and claim denial rates — you can prioritize negotiations with the most impactful insurers, diversify payer relationships, and adjust service offerings strategically. MGMA DataDive subscribers have access to national benchmarks for payer mix in the Cost and Revenue data set.

How physicians are paid

Physicians and administrators should carefully evaluate reimbursement methodologies when negotiating contracts with payers. The core of these negotiations is determining how and when the payer compensates physicians for services provided to patients and ensuring that payment terms align with the practice’s financial sustainability.

Payers use various reimbursement structures, which can significantly impact revenue flow and risk exposure. Below are the most common methods:

1. Fee-for-service (FFS)

Under a fee-for-service model, physicians are reimbursed for each service or procedure performed based on a negotiated fee schedule. This remains the most common payment structure, particularly in PPO and traditional Medicare plans.

- Contract consideration: Ensure that reimbursement rates align with market benchmarks (e.g., Medicare Fee Schedule, commercial payer benchmarks).

- Risk factor: Subject to utilization reviews, prior authorizations, and potential claim denials.

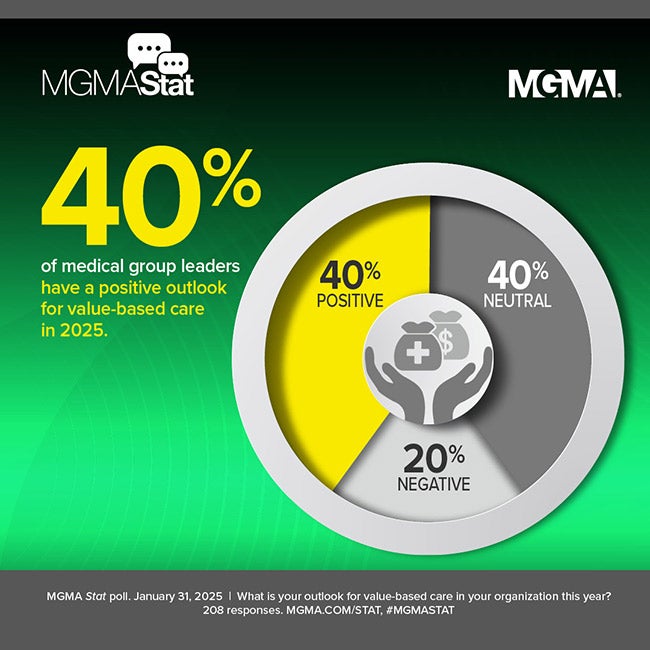

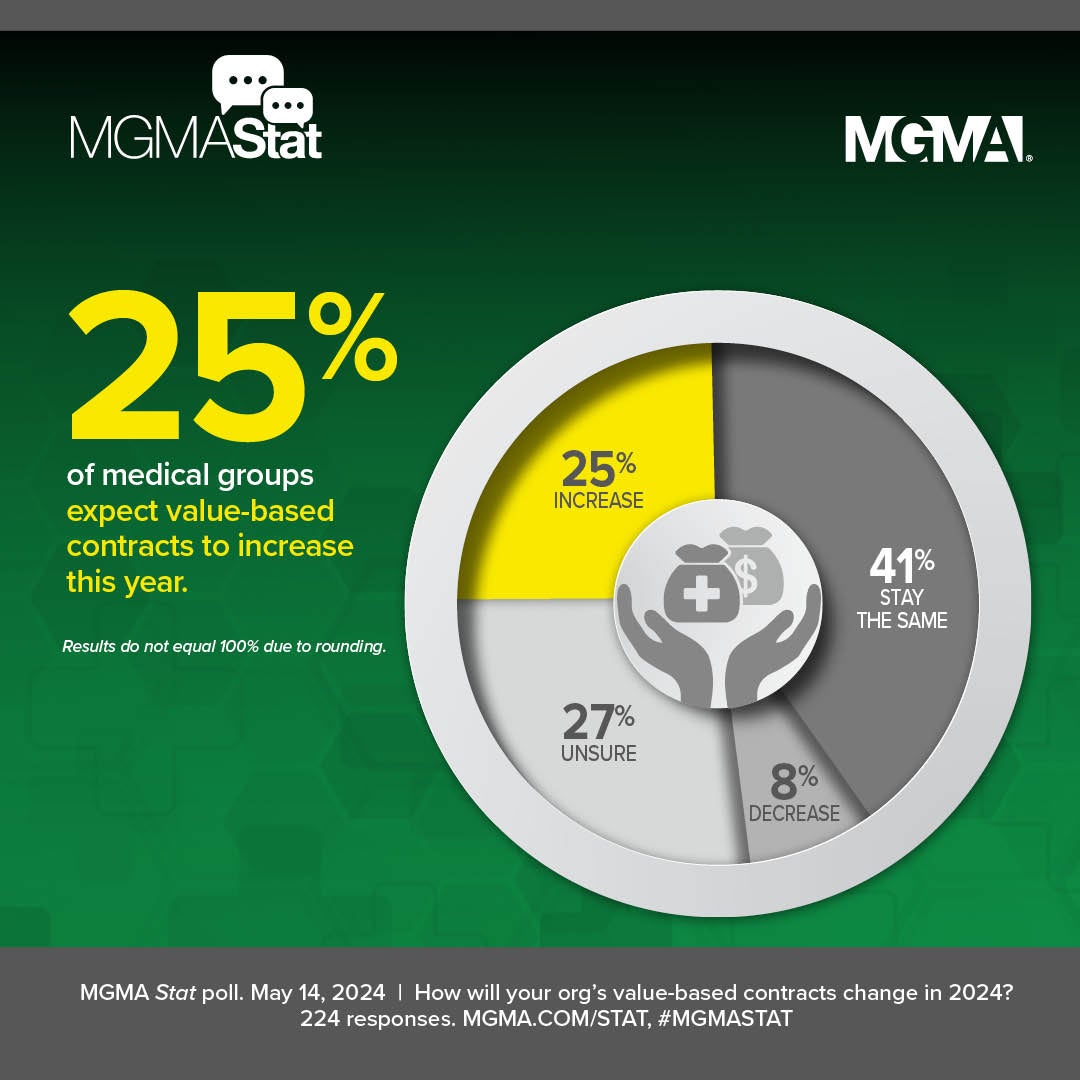

2. Value-based and performance-based payments

Many contracts include quality-based incentives tied to clinical performance metrics. Physicians may earn additional compensation for achieving predefined goals, such as:

- Improved diabetes management (e.g., controlled A1c levels)

- Lower hospital readmission rates

- Higher patient satisfaction scores

Common value-based payment models include:

- Pay-for-Performance (P4P): Providers receive bonuses or penalties based on quality measures.

- Shared Savings Models: Physicians share in cost savings if they reduce spending while maintaining quality.

- Alternative Payment Models (APMs): May include bundled payments, capitation, or population health management contracts.

3. Bundled payments

In a bundled payment model, payers provide a single, fixed payment for an entire episode of care (e.g., joint replacement surgery). Payment may be made:

- Prospectively (prepaid before the procedure, requiring cost management by the provider)

- Retrospectively (adjusted after services are rendered based on actual costs and quality outcomes)

- Contract consideration: Define which services are included in the bundle, risk-sharing terms, and dispute resolution mechanisms for unexpected costs.

4. Capitation and per-member-per-month (PMPM) payments

Capitation involves fixed per-patient payments, where physicians receive a set amount per member per month (PMPM) regardless of services provided. This model is common in HMO plans and some Medicare Advantage contracts.

- Full capitation: The provider assumes full financial risk for patient care.

- Partial capitation: The provider is responsible for specific services (e.g., primary care but not hospitalizations).

- Risk factor: Practices must manage costs efficiently since payments remain fixed, regardless of patient utilization.

Why payment structures matter in contract negotiations

A contract’s reimbursement model determines financial risk, revenue predictability and cash flow stability. Physicians should negotiate:

- Competitive fee schedules (for FFS models)

- Fair risk-sharing terms (for capitation and bundled payments)

- Transparent quality metrics (for value-based contracts)

A well-negotiated contract ensures sustainable revenue while mitigating financial risks associated with payer reimbursement policies.